One of the primary reasons I gravitated towards Category Entry Points when they were first introduced by Jenni Romaniuk and the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute (EBI) several years ago was due to their usefulness as a framing device for creating a much more pointed strategy. Due to the prevalence of EBI thinking and the impact of the little red book, much of Sharp’s great work on maximising salience suffered a loss of nuance when the rubber hit the road. It felt like many brand strategies were oversimplified to a simple need of increasing awareness (via maximising reach). But there was a very important missing layer to this. Context. Moreover, mental availability in context.

At the most basic level, planning via the CEP shifts the thinking from vague, top-level (often difficult to achieve) objectives such as “increase awareness by X%” to something much more actionable, tied explicitly to building mental availability in context. A CEP focus enables you to prioritise CEPs (moments, occasions, associations, etc.) that offer your brand the best opportunity for growth. They also provide real guidance and clarity to all teams about what you’re ultimately going after.

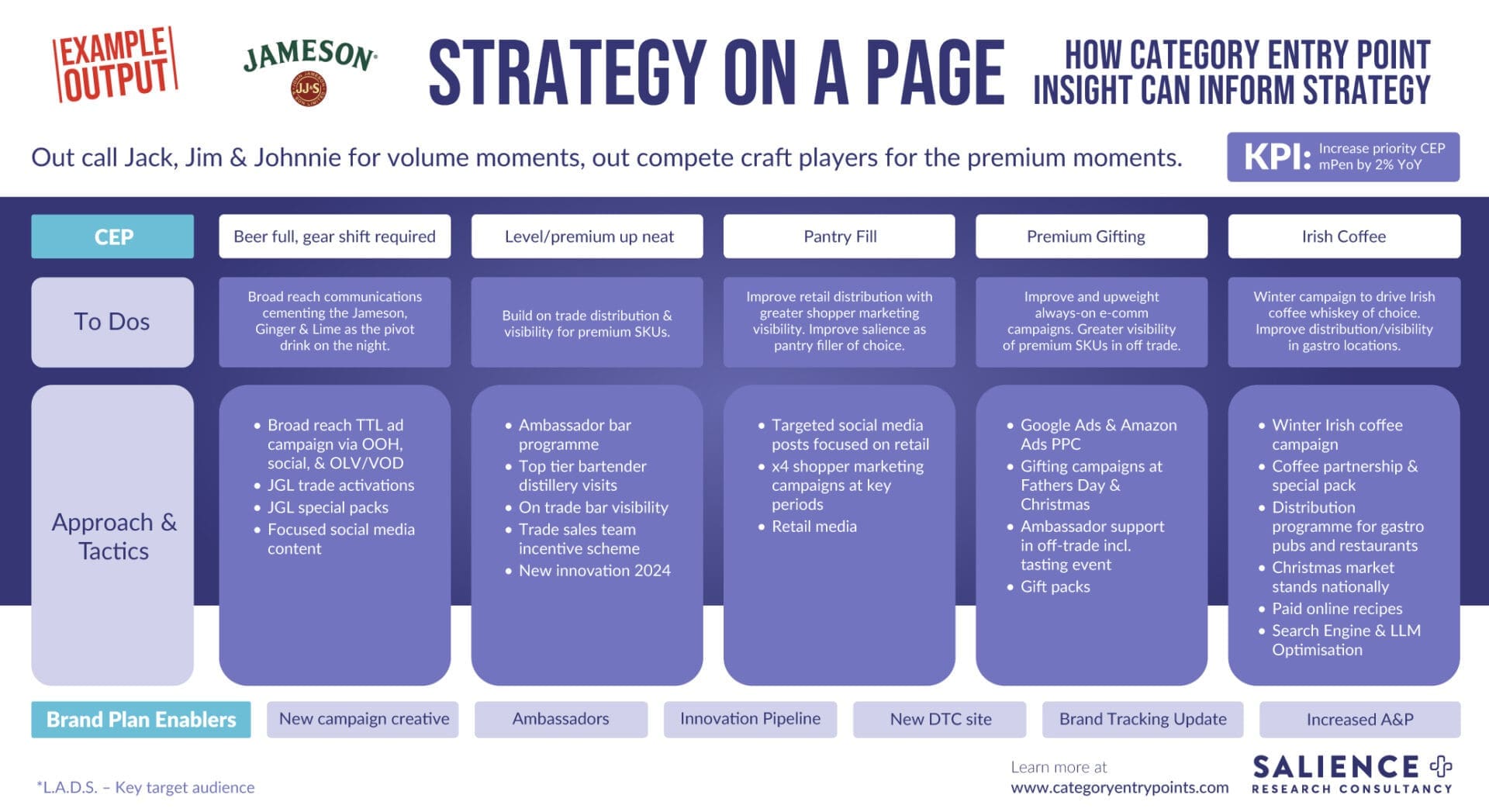

The following is an example and walkthrough of what this could look like for Jameson Irish Whiskey, based on observations of some areas they play in. As an Irishman, it’s a brand I’ve long admired and drank (no Irish clichés here). It’s illustrative, not real, based on some of their activations in the wild, and an example of how CEPs can be used to inform a brand plan.

Firstly, Jameson is a big brand. And big brands are big because they compete across many CEPs, which should ultimately be the aim, but some prioritisation and focus are always required. The first step in using Category Entry Points is in identifying the more important CEPs in the “category.” This can be done via a number of methods (our Category Entry Point research solution involves quantitative research, using bespoke diary-style surveys combined with some pretty nifty statistical analysis). One of the first steps, however, before you map out your CEPs, is actually identifying the “category” where you compete. If Jameson were to compete solely within the Irish Whiskey category, it would miss out on significant opportunities in adjacent categories and CEPs. Jameson doesn’t just compete with Tullamore D.E.W. and Bushmills in Irish, or Jack & Jim in whisk(e)y, it competes with G&Ts for refreshing moments or even a golf sweater for your dad on Father’s Day, and many other categories across CEPs (Read more about the importance of the “category” in CEP planning here).

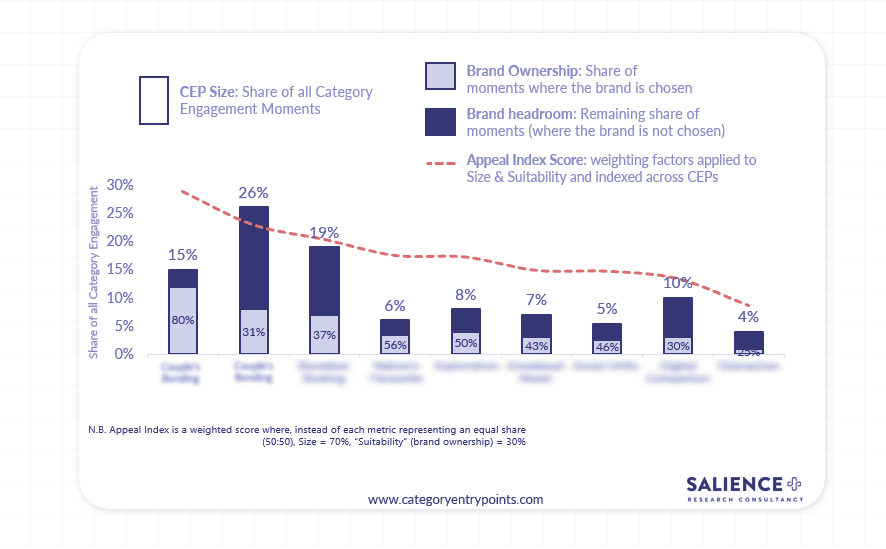

Once the broad set of CEPs is identified, the next step is prioritisation, which involves selecting the most attractive CEPs to target and focus on. For this, our approach utilises a custom Appeal Index Score which takes into account not only the size of the CEPs, but several other variables which can include things like brand favourability, potential margin, distribution and growth headroom amongst other factors.

Our approach to Category Entry Point prioritisation

Category favourability/permission is also an interesting variable here, especially when looking at CEPs that straddle multiple adjacent categories. A CEP may indeed be huge, but your brand/category might struggle for a foothold. For example, take a “Post dinner digestive” type CEP related to alcohol. It could be pretty massive, but heavier stout/beer brands may struggle versus, say, gin, liquor, or cognac brands.

Following this prioritisation exercise, you should end up with a handful of target CEPs as per the below. For global brands, this approach allows you to step load your priority CEPs based on market stage, for example, focusing on a few CEPs in seed or early-door markets (or those with smaller budgets), and then expanding this over time as the brand gains a foothold (and as A&P investment increases through compounding improvements).

It’s all well and good to try to go after everyone and everything when you are a brand behemoth; however, 99% of brand plans need real focus, and this becomes further complicated when dealing with different markets at different stages of maturity, with varying budgets, and global-local tension playing into the mix.

What I particularly like is how priority CEPs can be used as the key pillars (or levers), or simply put, the most important things you need to do as part of a brand plan, and from here, you have the key “to-dos”.

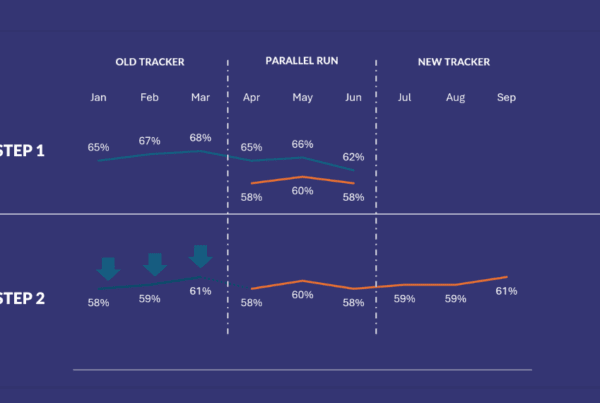

Each pillar/CEP can then have clear, specific objectives tied to it. Tactics can then flow from these CEPs, and even essential areas, such as distribution gains or innovations, can be tied back. Finally, each pillar is then easily measurable through ongoing CEP tracking. For example, the performance of the brand within the Irish Coffee space (measured by consideration/awareness within the context of Irish Coffee).

Of course, this type of approach will vary depending on whether it’s a global strategy or indeed local brand plan with other factors like pricing, positioning, distribution, target audience, DBAs, distribution, etc. handled elsewhere in more detail.

You might also think that this framing device is also somewhat limiting in terms of the number of CEPs; however, you can only communicate so much to those “doing the doing” on the ground, and resources and budget can only be spread so far. Even with this type of focus, there will always be spillovers, from a mental & physical availability perspective, into neighbouring or lower priority CEPs. For example, a focus on “Pantry Fill” will hopefully zero in on this CEP but will naturally target a lot of other shopper occasions. While a Father’s Day campaign would not only aim to improve salience & short-term sales for this occasion, it would also naturally improve brand salience for other related gifting occasions.

Another layer that can be added to this is also related to whether the activity is more long-term or short-term focused (i.e. brand building for the long term, or sales activation for the short term). This example suggests that the first CEP is the focus for broader reach advertising (such as this campaign), but depending on your CEPs, you may see that a large-scale, broad reach campaign targets multiple CEPs, depending on their relationship or similarity. There are many ways to approach this, which will really depend on the CEPs and where you bottom out on them in terms of size and level. We often use a dendrogram as an output of our CEP research, showing the different branches & clusters of CEPs, which is helpful for informing campaigns, campaign vignettes or creative messaging hierarchy. With reference to the below, a big brand campaign could aim to focus and target on a branch, grouping, cluster or individual CEP level.

The beauty of working with CEPs lies in their ability to bring structure to what can otherwise feel like chaos. They help teams see the wood for the trees, not just who to reach, but when and why. Brands that build around these moments become the ones that come to mind first when it matters most, and that is what good marketing plans should ultimately aim to do.

To learn more about using Category Entry Points, check out our resources & blog here, or get in touch to dive deeper into the topic.